In a surprising twist to the urban farming narrative, a study challenges the widely-held belief that urban agriculture (UA) is a beacon of sustainability. Despite its celebrated diversity and perceived lower environmental impact, those charming community gardens and small-scale farms emit six times more carbon dioxide equivalents than their conventional counterparts.

“Urban farms … are typically celebrated for their diversity, low rates of fertilizers and pesticide use, and reduced food transport emissions…[and are] often seen as a hopeful counter to the resource-intensive monoculture model of conventional farms…”

- Emma Bryce, The Anthropocene

A study in Nature Cities attempts to measure the carbon footprint of urban agriculture (UA), pointing out that it is not nearly as green and carbon-reducing as we have fantasized. I’ve written on urban farming, primarily about more high-tech approaches involving vertical farming that increases yield per square foot, artificial lighting, and hydroponics. This study considers the more low-tech approaches in open-air, soil-based models.

The data used to draw conclusions comes from standard measures of fruit and vegetable greenhouse gas emissions and, more specific survey obtained, information on the inputs and outputs of these three types of low-tech UA. They identified 73 sites across the EU, UK, and US, categorizing these farms as

- Commercial enterprises, managed by professional farmers, producing enough vegetables to feed 40–50 people annually.

- Individual gardens producing food for their owners and friends.

- Collective gardens supported primarily by volunteer labor or non-profit support, producing food for community benefit, roughly enough for 15 people but usually divided up to partially feed more.

Results

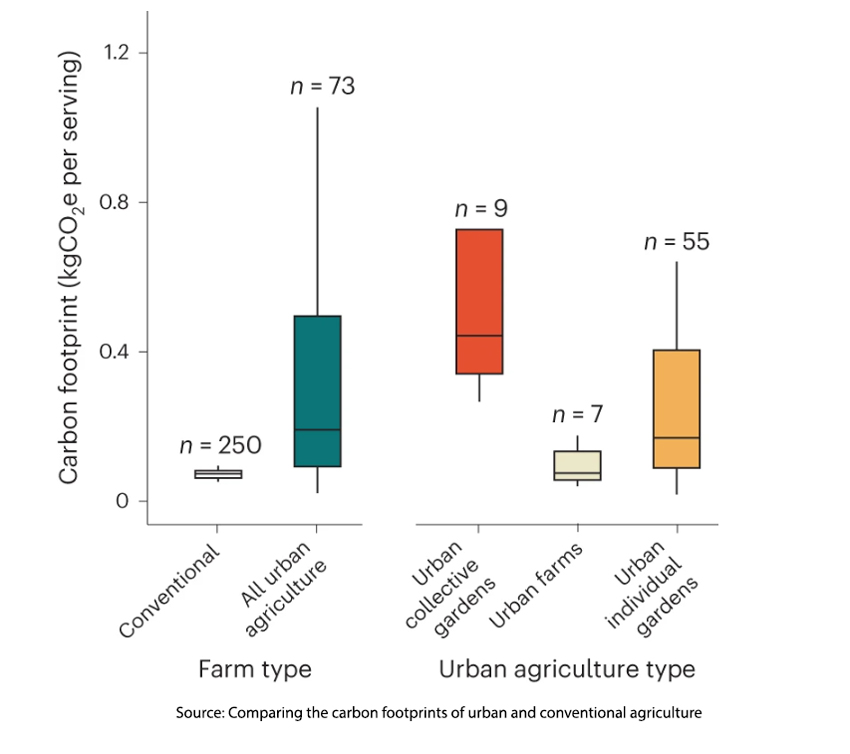

UA produces six-fold more CO2 equivalents than comparable conventional farming. 0.42 kilograms carbon dioxide equivalents (kgCO2e) vs. 0.07 kgCO2e per serving for conventional produce. Collective gardens had the most CO2 equivalents, those professionally managed urban farms the least, with at least some of those farms “carbon-competitive” with conventional farming

UA produces six-fold more CO2 equivalents than comparable conventional farming. 0.42 kilograms carbon dioxide equivalents (kgCO2e) vs. 0.07 kgCO2e per serving for conventional produce. Collective gardens had the most CO2 equivalents, those professionally managed urban farms the least, with at least some of those farms “carbon-competitive” with conventional farming

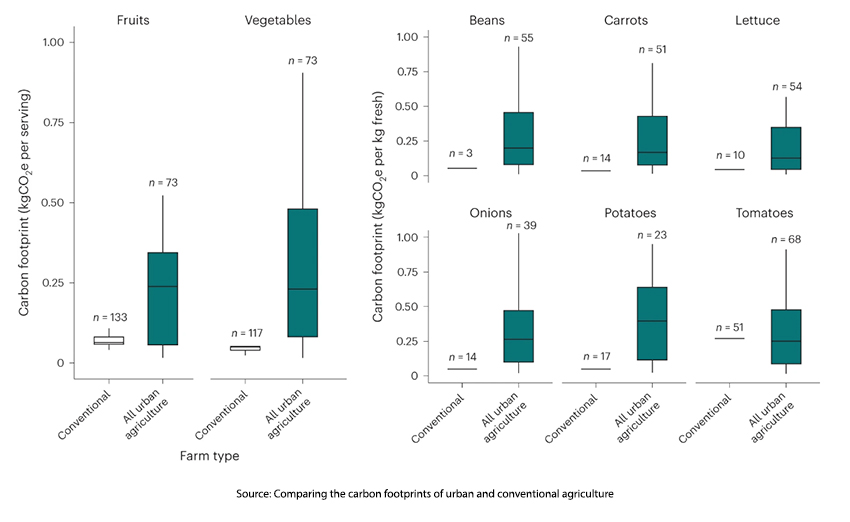

Urban agriculture produced more CO2 equivalents for fruits and vegetables as a group or considered independently. The only case that could be made for UA was in the case of tomatoes, a perennial garden favorite. Where “carbon-intensive greenhouses that  supply most tomatoes” to the cities under investigation once again made tomatoes “carbon competitive.”

supply most tomatoes” to the cities under investigation once again made tomatoes “carbon competitive.”

A similar competitiveness was seen with more specialized vegetables, e.g., asparagus, where the transport costs, often across hemispheres, made the urban version carbon equivalent to conventional farming.

17 of the 73 sites did outperform conventional agriculture. Researchers identified three” best practices” driving these “climate-friendly” sites.

Infrastructure – the largest source of carbon emissions in low-tech UA, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the impact. Constructing sheds, raised beds, and water systems all generate carbon dioxide, which in the world of carbon counting can be “amortized” over a lifetime of use. The environmental impact will be greater because urban farms are sustained for shorter periods.

Reuse of urban wastes - Climate-friendly sites found savings by reusing building materials considered urban waste. But that is a one-time savings, and it is doubtful that commercial farms will choose that as a source of their infrastructure. Compost is one of urban agriculture’s most well-known waste management reducing the reliance on potting soil and synthetic fertilizers. As you might anticipate, collective gardens used no synthetics, while commercial farms used significantly more, but “still a statistically significant saving relative to conventional systems.” Composting does come with a caveat,

“The carbon footprint of compost grows tenfold when methane-generating anaerobic conditions persist in compost piles.”

Unfortunately, this is frequently the case with small-scale composting, as is found in those individual gardens.

Social benefit – this is the squishy factor in the researchers’ calculation. While acknowledging that the allocation of impacts is challenging, they suggest that when “more than 90% of infrastructure impacts are allocated to non-food services,” UA outperforms conventional agriculture. Of course, growing ornamental flowers or using the facilities to host community social events does not necessarily meet the primary job of urban farms – producing food. One can additionally put their fingers on the scale by incorporating the “wellness” attributable to those fresh fruits and vegetables in improving the health of individuals served by UA. That is how one study in the UK found

“…social benefits, such as improved well-being and reduced hospital admissions, accounted for 99.4% of total economic value generated on-site.”

I will leave the reader to draw their own conclusions about the current value of low-tech urban agriculture. The researchers did their best to continue the narrative of eating locally to support both the community, which is not a bad idea, and mitigate climate change, which seems more aspirational than practical.

“Our results show that today’s UA generally produces more GHGs than conventional agriculture, although this needs additional clarification … Meanwhile, all UA sites must extend the useful life of infrastructure, reuse more materials, and maximize social benefits to become carbon-competitive with conventional agriculture. … important work remains to be done to ensure that UA benefits the climate as well as the people and places it serves.”

Source: Comparing the carbon footprints of urban and conventional agriculture Nature Cities DOI: 10.1038/s44284-023-00023-3