Once we became aware of our mortality, we wanted to know when death was upon us. While we have forsaken predictions by chicken bones or auguries, today we attempt the same predictive magic. That's at least at the population level, using new chicken bones like our co-morbidities or a frailty index. It should be no surprise that we have enlisted our latest oracle: A.I.

Disease

Exa-cel, a new CRISPR-based treatment, modifies the genes of the patient's stem cells to induce them to produce fetal hemoglobin.

Doctors use “diagnostic” labels to describe a condition or constellation of symptoms and signs before determining treatment or rendering a prognosis. Diagnostic criteria generally remain static and serve as a collective reference point for the medical world. Not so for the diagnosis of “excited delirium.” Not only has the meaning of “excited delirium” morphed over time, but the legal community has conscripted it for non-medical purposes, like defending claims of excessive force by police officers. Recently, the medical community rejected this use and “revoked” the diagnosis. Who benefits?

In this conversation on "CBS Eye on the World," John Batchelor and I discuss the development of a universal vaccine to prevent COVID-19. John has received multiple COVID-19 vaccinations and was curious about the concept of a universal vaccine that would protect against all – even future – variants of the virus.

We know the beat of our heart varies over time, increasing with exertion and slowing with rest or meditation. But, stable as those variations may appear, they vary even within those intervals. Dr. George Lundberg, former long-time editor of JAMA, muses about those variations – termed heart rate variability – and what they might tell us.

In order to accurately capture the nuance of an article, especially those about scientific and medical matters, headline writers and editors should read the piece before composing a headline.

We know stress can be dangerous, although treatment is not lacking. Pharmaceuticals abound, and more are in development. But reports are emerging that drugs may be addictive, they don’t work well in mild or moderate cases, and it's hard to wean off them. What’s a patient to do?

The uptake of the current COVID vaccine is running at about 7% of the U.S. population. Pfizer is taking a significant write-off. After the pandemic, our trust in vaccinations has reached a nadir. It's a far cry from our behavior concerning smallpox in 1947 when, over eight days, over 4 million New Yorkers were vaccinated. Or compared to 1961, when 90% of the at-risk population got vaccinated against polio.

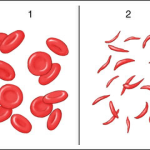

While largely ineffective medications for the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease have gotten a great deal of press, an “orphan” disease – sickle cell disease – is in a similar situation. It is a devastating disease, and there seems to be a gene treatment on the horizon, one that comes with risks and benefits. How do patients calculate what to do?

Answer: It could be. Stress kills. Rarely, but not never. And then there is anxiety, which subsumes a host of related diagnoses. The terms are often co-mingled, with the latter tending to diffuse the dangers of the former. Let’s take a deeper look.

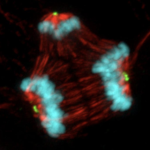

This could be big. All physicians or cancer researchers have been taught forever that a certain class of cancer drugs works by stopping mitosis, hence cancer cell division. However, a group at the University of Wisconsin discovered that everything we thought we knew about drugs like Taxol and vincristine - decades of textbooks - is wrong. The ramifications could reshape cancer drug research.

At the beginning of the year, the CDC and FDA noted “a preliminary safety signal for ischemic stroke among persons aged ≥65 years” who had received the COVID bi-valent vaccine, as well as a similar but "higher" signal in individuals receiving the influenza vaccine at the same time. Now, a study has confirmed that safety signal.